Rules guarding other planets from contamination may be too strict

As more missions target the moon, Mars and other places, scientists want to update guidelines

Some policies for protecting the moon, Mars and other places in the solar system from contamination by visiting missions may be too strict.

That’s the conclusion of a 12-expert panel commissioned by NASA to review voluntary international guidelines for keeping space missions from polluting other worlds with earthly life, and vice versa. These guidelines are recommendations from the international scientific organization COSPAR, which for decades has set and revised policies for spacefaring nations (SN: 1/10/18).

With NASA sending a sample-collection mission to Mars next year (SN: 11/19/18), and other government agencies and private companies also preparing for trips to the moon (SN: 11/11/18), planetary protection guidelines “are in urgent need of updating,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in a teleconference coinciding with the review’s October 18 release. “We want to respect the integrity of the places we go and protect our home planet” from any contaminants that might be brought back, he says. But the report found that current rules could make future missions unnecessarily complex or expensive.

For instance, current guidelines treat the whole moon as a potentially interesting site to investigate the origins of life. That means every landing mission is supposed to submit documentation to COSPAR detailing where it went and what it did. But apart from a few regions, such the lunar south pole which may have water ice reservoirs (SN: 7/22/19), the moon holds little interest for investigating the chemical evolution of life, said panel chair and planetary scientist Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., during the teleconference. So many places may not need protection.

At least one astrobiologist cautioned, however, against relaxing current guidelines too much. Spacecraft landing in areas deemed sterile could still contaminate areas that are potentially interesting for astrobiology, says John Rummel of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. If a lunar probe crashes on the moon’s surface, “you end up with material that’s taken into the lunar atmosphere and deposited in the cold traps at the south and north anyway,” he says. “You don’t even have to land at the south pole to affect [it].”

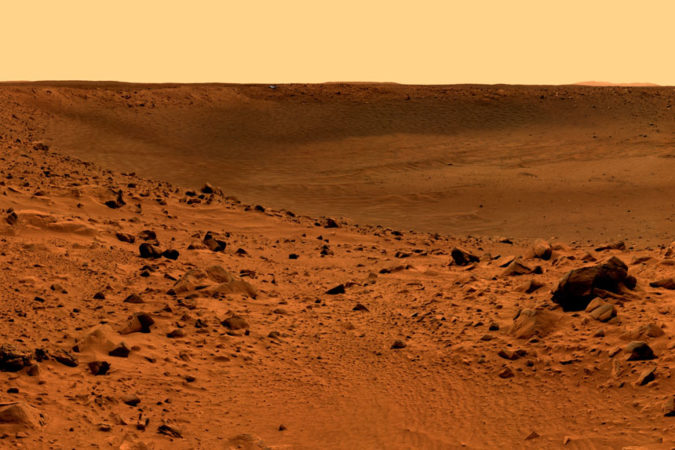

In its report, the review panel also recommended reassessing contamination risks across Mars. Missions to the Red Planet have been designed to meet rigorous sterilization standards that often involve exposing spacecraft components to heat, chemicals or harsh radiation. But experiments have suggested that Earth microbes probably would struggle to survive and spread on many parts of Mars. So such deep cleaning may not be needed, according to the report.

The report suggests that specific areas of Mars should be identified as high-priority zones for seeking past or present life. Other areas could be designated as human exploration zones, where microbes brought by astronauts wouldn’t pose such a problem. “While some places on Mars have high interest for understanding the potential for past life on Mars, or even prebiotic development of life … not all places on Mars have that potential,” Stern said.Astrobiologist Alberto Fairén of Cornell University welcomes the possibility of adding nuance to the “extremely restrictive” protection guidelines for Mars. He and colleagues recommended a few high-priority astrobiology zones in Advances in Space Research in March, including lakes of liquid water possibly hidden under ice sheets (SN: 12/17/18).

Rummel, of the SETI Institute, takes a more conservative view. “There are undoubtedly places on Mars where Earth microbes aren’t going to grow,” he says. The rub is understanding Mars in enough detail to know where those spots are with total confidence. “We don’t know enough about Mars, in my opinion, [to categorize] most of it.”

Beyond reevaluating the risks of contaminating the Martian surface, the NASA report also considers rules for bringing samples back to Earth. Current guidelines stipulate that Red Planet rocks should be sterilized or to undergo biohazard testing before they can be handed out for analysis. Such precautions “lack a fully rational basis,” considering how much Martian material has landed already on Earth, the report says. “Earth and Mars have been exchanging meteorites for billions of years with absolutely no planetary protection,” Stern pointed out.

NASA now will consider the report in updating its own standards of practice for planetary protection, but the process for incorporating these suggestions into COSPAR’s guidelines “is not well-defined,” the report says.

0 comments :

Post a Comment